Batik

Indonesian Batik

A Cloth With Little Dots

The Heritage

Batik is an art form with a history that stretches back through the ages, covering various cultures and civilisations in its intricacy, its beauty, and its ability to weave stories and identities with every delicate detail. The word itself is thought to be a derivation of ambabatik - ‘a cloth with little dots, and today. It’s one of the most instantly recognisable and widely loved artisanal design crafts.

The practice of Batik can be traced back over 1,500 years to ancient designs of the Middle East and Egypt, yet while many cultures have displayed mastery of the technique, few - if any - have perfected the craft as impressively as the artisans of Java. On this Indonesian island, batik is taken to the heights of intricacy, and tribal identities, ancient stories, and countless symbols are highlighted on textiles with a signature dye resistance technique.

Despite its inherent depth and complexity, the traditional batik tools which endure to this day remain effortlessly simple. Javanese batik artists utilise a canting - a local innovation which is little more than a spouted copper container - to realise their beautiful and enchanting designs.

The Prints

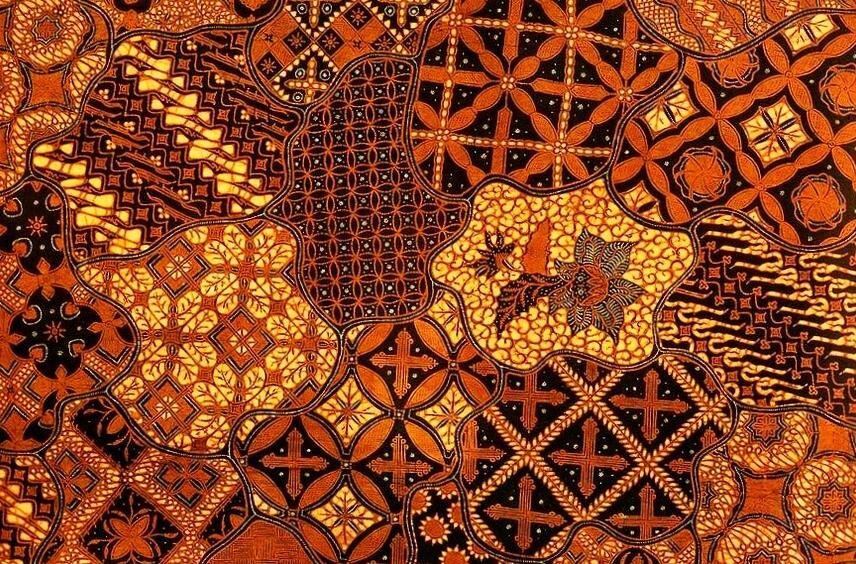

By its very nature, Batik lends itself to a broad spectrum of different styles, designs, and motifs. However, it can generally be divided into two distinct categories: the more historic geometric motifs, and the more recent arrival of free-flowing, freeform designs, often inspired by natural forms and the intricate patterns inherent in woven textures.

In the ‘writing’ of batik designs, artisans have the opportunity to reflect facets of their culture and heritage onto cloth. As such, distinct batik traditions have arisen across the generations in particular parts of the world. In Java alone, we can see the emergence of individual recognisable batik styles, taking their inspiration from their regional and tribal histories; the central part of the island focuses primarily on traditional colours and patterns, whereas northern Javanese batik takes its cues from Chinese design idioms, rich in colour and boasting intricate motifs of flowers and clouds.

Indonesia’s Islamic artistic traditions can be felt in the Ceplok batik style, also common to the island. As Islamic art is based primarily on sacred geometric forms and calligraphy, Ceplok is based entirely on motifs of squares, circles, stars, and other repeating shapes. Perhaps the most ancient and enduring batik style in Java is Kawung. Once the royal court’s preserve of 13th-century temple design and decoration, this beautifully elegant patterning consists of intersecting circles, often formed into delicate floral motifs.

The batik art form is a technique that allows for expression, inspiration, beauty, simplicity, and complexity. Batik traditional designs enchant and inspire others.

The Colours

Few components of a design signify heritage and the roots of artisanship as much as colour. When exploring the colours of traditional batik, and especially central Javanese batik, we uncover colours made from an array of natural ingredients and dyes, primarily beiges, browns, blues, and black.

The most ancient colours were the deep and glorious blue tones derived from the precious leaves of the Indigo plant, which skilled craftspeople mixed with molasses sugar and lime, and sometimes the sap of the Tinggi tree - a natural fixing agent - before leaving to stand overnight. Indigo allowed designers to explore the full range of blue tones and hues. Lighter shades were achieved by leaving the cloth in dye baths for shorter periods. Intense and rich darker tones would be obtained by dyeing for several days and often submerging and re-submerging the fabric up to ten times before each nightfall.

The bark of the Soga tree gives the gift of the second colour used in traditional batik, a dye that ranges from pale yellow to dark brown. Darker red colours are achieved by processing the leaves of Morinda Citrifolia, a plant that allows for creating a beautiful dye known locally as mengkuda. Once the dyes were assembled and the dye baths had been made, the artisan’s skill dictated how powerful or delicate the final hue would become. Different dyeing periods produced different intensities. Colours could be mixed to form evocative new tones, leaving brilliant, intricate patterns.

Photo source: unknown